|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TRIBAL AFRICAN ART

Mali

The

Bambara numbering 2,500.000 million form the largest ethnic group within Mali. The

triangle of the Bambara region, divided in two parts by the Niger River, constitutes the

greater part of the western and southern Mali of today. The dry savanna permits no more

than a subsistence economy, and the soil produces, with some difficulty, corn, millet,

sorghum, rice, and beans. Their traditions include six male societies, each with its own

type of mask. Initiation for men lasts for seven years and ends with their symbolic death

and their rebirth. Nearly every Bambara man had to pass through these societies in

succession, until, upon reaching the highest rank, he had acquired a comprehensive

knowledge of ancestral traditions.

The jo

society has become a sort of framework for other initiation society. Until a few decades

ago, initiation was obligatory for every young man. Jo initiations take place every

seven years, after candidates receive six years of special training. During this time, the

young men go through a ritual death and live one week in the bush before returning to the

village. There they publicly perform the dances and songsthey have learned in the bush,

and receive small presents from spectators. After a ritual bath that signals the end of

their animal life, the new initiates become “Jo children.”

Initially

the ntomo was a society for uncircumcised boys. Today it closely resembles various

Western associations in its bureaucratic structure and its administrative and membership

fees. There are two main style groups of their masks. One is characterized by an oval face

with four to ten horns in a row on top like a comb, often covered with cowries or dried

red berries. The other type has a ridged nose, a protruding mouth, a superstructure of

vertical horns, in the middle of which or in front of which is a standing figure or an

animal. The ntomo masks with thin mouths underscore the virtue of silence and the

importance of controlling one’s speech. During their time in ntomo the boys

learn to accept discipline. They do not yet have access to the secret knowledge related to

korè and other initiation societies.

The korè

society is perceived by the Bambara people as the “father of the rain and

thunder.” Every seven years a new age-set of teenagers experiences a symbolic death

and rebirth into the korè society through initiation rituals whose symbols relate

to fire and masculinity. Initiations take place in the sacred wood, where the youths are

harassed by elders and the clown-like performers called korédugaw. In their

general form and detail, a group of korè masks conveys concepts such as knowledge,

courage, and energy through the representation of hyenas, lions, monkeys, antelopes, and

horses. In addition there are masks of the nama, which protect against sorcerers.

The komo

is the custodian of tradition and is concerned with all aspects of community life --

agriculture, judicial processes, and passage rites. Its masks are of elongated animal form

decorated with actual horns of antelope, quills of porcupine, bird skulls, and other

objects. Their headdress, worn horizontally, consists of an animal, covered with mud, with

open jaw; often horns and feathers are attached. Masks of the kono, which enforces

civic morality, are also elongated and encrusted with sacrificial material. The kono

masks were also used in agricultural rituals, mostly to petition for a good harvest. They

usually represent an animal head with long open snout and long ears standing in a V from

the head, often covered with mud. In contrast to komo masks, which are covered with

feathers, horns and teeth, those of the kono society are elegant and simple.

The tji

wara society members use a headdress representing, in the form of an

antelope, the mythical being who taught men how to farm. The word tji means

“work” and wara means “animal,” thus “working

animal.” There are antelopes with vertical or horizontal direction of the horns. In

the past the purpose of the tji wara association was to

encourage cooperation among all members of the community to ensure a successful crop. In

recent time, however, the Bambara concept of tji wara has

become associated with the notion of good farmer, and the tji wara

masqueraders are regarded as a farming beast. The Bambara sponsor farming contests where

the tji wara masqueraders perform. Always performing

together in a male and female pair, the coupling of the antelope masqueraders speaks of

fertility and agricultural abundance. According to one interpretation, the male antelope

represents the sun and the female the earth. The antelope imagery of the carved headdress

was inspired by a Bambara myth that recounts the story of a mythical beast (half antelope

and half human) who introduced agriculture to the Bambara people. The dance performed by

the masqueraders mimes the movements of the antelope. Antelope headdress in the vertical

style, found in eastern Bambara territory, have a pair of upright horns. The male

antelopes are decorated with a mane consisting of rows of openwork zigzag patterns and

gracefully curved horns, while the female antelope supports baby antelopes on their back

and have straight horns. The dancers appeared holding two sticks in their hands, their

leaps imitating the jumps of the antelopes. From the artistic point of view the tji

wara are probably the finest examples of stylized African art, for with a delicate

play of line the sensitive carvings display the natural beauty of the living antelope.

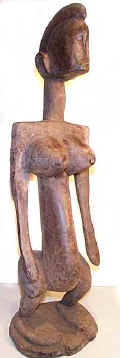

In

traditional African societies, a childless marriage is a grave problem. Further,

childlessness seems to be the wife’s problem to resolve. Women with fertility and

childbearing problems in Bambara society affiliate with gwan, an association that

is especially concerned with such problems. Women who avail themselves of its

ministrations and who succeed in bearing children make extra sacrifices to gwan,

dedicate their children to it, and name them after the sculptures associated with the

association. Gwan sculptures occur in groups and are normally enshrined. An

ensemble includes a mother-and-child figure, the father, and several other male and female

figures. They are considered to be extremely beautiful. They illustrate ideals of physical

beauty and ideals of character and action. The figures are brought out of the shrine to

appear in annual public ceremonies. At such times, the figures are washed and oiled and

then dressed in loincloths, head ties, and beads, all of which are contributed by the

women of the village. The size of the statues may vary from 12 inches to 4 feet. The

figures are usually with a dignified air. Some have the arms separated from the body, flat

palms facing forward, the hands sometimes attached to the thighs. They may have crest-like

hairdos with several braids falling on their breasts. In the same style, representations

of musicians and of lance-carrying warriors are found. There are also carvings with Janus

head. Ancestor figures of the Bambara clearly derive from the same artistic tradition, as

do many of those of the Dogon. Rectangular intersection of flat planes is a stylistic

feature common to Bambara and Dogon sculpture.

There are

also reliquary figures in form of a woman, having an oval cavity below the breasts,

marionette figures, and others.